- Home

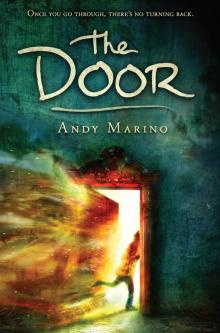

- Andy Marino

The Door

The Door Read online

For my parents

CONTENTS

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE

CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

COPYRIGHT

The spiral staircase to the top of the lighthouse was full of invisible traps. Hannah Silver ascended by skipping the odd-numbered steps. At step sixteen — halfway up — she planted both feet in a decisive hopscotch landing and wiggled her fingers and toes. No pain. She examined her arms and legs.

You’re fine, Belinda said. If Belinda were to appear in real life, instead of in Hannah’s head, she would smell like beef stew and wear a cream-colored floral housecoat. Walk normally. You’re too old for this game.

“I know, I know, I know,” Hannah said, but the rule was hard to defy — even though, at twelve years old, she knew better.

Take them one by one, urged Belinda. Seventeen, eighteen, nineteen. All the way up, just like that.

“Chalkdust!” Hannah said, stamping her foot. The old iron staircase protested with a metallic groan. Chalkdust was a swear in Muffin Language, which she had been developing since she was old enough to talk. She was the world’s foremost expert on its grammar and vocabulary; a fact she had verified on the library computer.

That’s because you’re the only person in the world who speaks it, Belinda reminded her.

“Crepuscular slurp,” Hannah muttered. Belinda backed off. Hannah rested her hand on the railing in her best imitation of a normal person on a staircase. The odd-numbered steps before her were like dark things lurking in the corners of a dream. If she squinted, she could make out all manner of medieval torture devices, dangling leather straps and rusted screws the size of baseball bats, waiting to ensnare her limbs.

Hannah reminded herself that she was never going to make it through her new school if it took her twenty minutes to climb a few steps. The junior high school in Carbine Pass was four stories high, and the elevator was teachers-only. She shuddered at the memory of her recent tour. The assistant principal had ushered Hannah and her mother inside the elevator and pressed the button for the top floor. The button was instantly surrounded by a thin circle of yellow light, like a tiny eclipse, while the others were rimmed in darkness.

Hit two and three, urged Nancy, Hannah’s mischievous inner twin. Light them up or the cable will snap and the elevator will fall!

Hannah’s left hand trembled. “Grenadine magnetism,” she whispered.

“Come again?” said the assistant principal.

Hannah’s mother put a reassuring hand on her shoulder, but it wasn’t enough. Hannah punched the buttons with desperate urgency.

“Huh,” said the assistant principal, writing something on a notepad.

Her mother must have worked some kind of magic, because Hannah wasn’t kicked out on the spot. One week from today, she would be homeschooled no longer. She had gotten her wish, and now she had to learn how to navigate stairs. Outside, waves battered the rocky cliffs. The sound was a foamy murmur inside the thick walls of the lighthouse; it helped. She lifted her right foot —

“Hannah!”

— and froze. Her mother was calling from the mossy garden path that connected the Silvers’ backyard to the lighthouse.

“Come meet our guests!”

Hannah turned the word over in her mind. Guests. It was practically meaningless. The few kids she knew from the Carbine Pass library were never allowed over. And anyway, with no TV, no computer, and no cell phone reception, Cliff House wasn’t exactly a prime hangout spot.

With a shameful blossoming of relief at the interruption, Hannah turned and descended the stairs, skipping fourteen, twelve, ten….

On the way down, these steps were trapdoors to a bottomless pit.

Hannah and her mother received their guests in a room with a big round window overlooking the sea.

“Hannah, I want you to meet Patrick.” Hannah’s mother introduced a tall, sandy-haired man with pale skin, friendly wrinkles at the corners of his eyes, and dark symmetrical blotches on his earlobes. He was dressed in a fine suit.

“Are you a lawyer?” Hannah asked, wondering if she was supposed to shake his hand, give a formal little bow, or just stand still.

“Retired,” he said, flicking his eyes toward Hannah’s mother and back to Hannah before indicating the boy at his side. “This is Kyle.”

Kyle was a year or two older than her, a teenager, with dark hair that swept in a perfectly accidental way across his eyebrows and along the tops of his ears.

“I’m not a lawyer, myself,” Kyle said, smiling at Hannah. “Anyway, hey.”

“Hey,” she said. Then she looked quizzically at her mother, who was wearing a bright orange dress that seemed to reflect light upward, bathing her face in a tropical glow.

“Patrick was a friend of your father’s,” her mother explained. “From a long time ago.”

That much was obvious — her father had died before she was born. Hannah studied Patrick’s face and tried to imagine a younger version of it. Hadn’t she seen a picture in one of her mother’s albums? Patrick and her father sitting on the porch, empty bottles cluttering the wicker table between them.

Quit staring! Belinda said.

Patrick’s earlobes weren’t stained by birthmarks, Hannah realized — they were tattooed with black ink. She transferred her gaze to Kyle and found that his lips were pressed together in a funny half smile. She felt like everyone was waiting for her to say something, which made her want to run away. At the same time, she felt helplessly rooted to her spot on the carpet.

Ask him what’s up with those marks on his ears, suggested Nancy.

“They are pretty weird,” Hannah agreed — and winced at having said it out loud. Being around guests was going to take some getting used to. Her mother settled a familiar reassuring hand on her shoulder and added a light squeeze.

“Patrick’s in Carbine Pass on a business trip,” her mother explained.

“Isn’t the point of being retired not to be in business anymore?”

“Yes and no,” Patrick said. “I’m no longer a lawyer, but I still have work to do.”

“My wild and crazy uncle Patrick is a consultant,” Kyle said.

One who consults, Nancy explained. They mostly work in outer space, I think.

Kyle went on. “It means he gets to travel around a lot, and sometimes if I don’t have school, I get to come.”

“My work affords me the freedom to visit old friends once in a while.” Patrick smiled at Hannah’s mother. “It really is wonderful to be back at Cliff House.” He took a deep, satisfied gulp of air. “I missed that smell. Sea and rocks and …” He flared his nostrils an

d inhaled gently, as if he were sniffing a glass of expensive wine. “Good memories. The strangest part about coming back after so many years is that it doesn’t really feel strange at all. Do you know what I mean?”

“No,” Hannah said. “I’m always here.”

“I guess in a way, so am I,” Patrick said.

Hannah looked at Kyle, who shrugged and seemed to roll his eyes without moving them very much at all. Hannah tried to make her own eyes say I know what you mean. Her mother’s vague pronouncements were often followed by a long, wistful glance out over the sea, and Hannah watched with satisfaction as Patrick and her mother both turned toward the window at the same time.

* * *

Patrick and Kyle stayed for dinner, and after the meal, it was left to Hannah and Kyle to clean up.

“I’ve never been this close to a real lighthouse before,” Kyle said, pulling a white plate from the landscape of steam and bobbing dishes that filled the sink. He scrubbed with a thick sponge while Hannah’s towel-draped fist made listless circles on a serving tray. She counted each revolution of the towel: six, seven, eight. Kyle worked at a smudge of stuck-on cheese, frowning with effort. Leanna Silver’s lasagna could be stubborn.

“I guess not that many people have them,” Hannah said.

As dinner had progressed through salad and bread and lasagna and ice cream, Hannah had found herself speaking almost nonstop to Kyle. He was much nicer than anyone she knew in Carbine Pass, and he seemed really interested in her life, rather than just waiting for his turn to talk. He didn’t ask how on earth she lived without TV and the Internet. He watched her eyes while she answered his questions, and seemed to file away her words in an important place in his head.

Even better, Nancy and Belinda hadn’t chimed in once. Usually they steered her conversations. That was a good sign. Maybe she was ready for public school.

“So is it really, like, yours?” Kyle asked.

“Before Cliff House was even built, my great-grandpa was the lighthouse keeper. He lived in this tiny little shed. It’s a whole story.”

Kyle scraped the last piece of cheese off the plate and handed it to her for drying. She set the tray on the counter and took the plate, resuming her lazy circles, starting her count over at one.

“I think we’ve got time,” he said, eyeing the pile of dirty dishes.

Her mother’s boisterous laugh drifted in from the dining room, where she and Patrick were having coffee. If the first surprise of the night was the sudden appearance of guests in the house, the second was the incredible change in her mother’s mood. Leanna Silver existed within a mild but steady gloom, as if the gray desolation of the North Atlantic had long ago seeped into her bones.

“That’s the old shed, right there.” Hannah pointed out the window above the kitchen sink. The whitewashed exterior of the lighthouse had soaked up darkness from the evening sky, and the forlorn shed at its base looked defiantly squat.

“Is there somebody in it?”

“Not for a really long time. We don’t need to warn boats away from the rocks anymore because radar got way better, and anyway they changed the shipping lanes. That’s part of the story.”

You’re telling it out of order, Belinda reminded her. Hannah jumped, fumbling the plate, catching it just in time. Belinda had been silent for almost two hours, and it startled Hannah to hear the old woman’s voice.

“He asked a question … shut up,” Hannah murmured, turning her head away from Kyle and setting the plate on the counter with a porcelain thud. She froze momentarily, trying to remember if she’d wiped the plate twenty-seven times or if she’d messed up and gone over.

Fifty-two! Nancy said. One of her favorite games was to yell random numbers when Hannah was trying to count in her head. Thirty-eight! Four hundred ninety-three!

Hannah closed her eyes and chased Nancy away.

Kyle said, “I can’t believe somebody lived in that little shed.”

“His name was Jackson Silver, and he really only slept there, because he spent all his time up in the lighthouse. That was back when lots of ships were sailing down the coast and smashing into rocks. Then after he got married he started building the main part of Cliff House. His son, Abraham, my grandpa, learned how to be a lighthouse keeper, too.”

“Is it really that hard?” Kyle asked. “I mean it’s just, like, turn the light on, turn the light off, right?”

“No, it’s — I don’t know. But there weren’t as many ships to watch out for anymore, so when Abraham was old enough he added more rooms to the house so he could start his own family. By the time Benjamin, my dad, was born, there was like no traffic out on the water at all, so he and my grandpa spent all their time working on the house. Then just my dad worked on it. By the time I got here, Cliff House was pretty big.”

Kyle had stopped washing dishes and was leaning against the sink, watching her tell the story. “That’s funny,” he said. “It’s like your family built this huge house because they were bored. You wouldn’t think part-time lighthouse keepers would have the money, you know? No offense.”

“They didn’t pay somebody to build the house.”

“You know what else is funny?” Kyle used his fingers to tick off names. “Jackson. Abraham. Benjamin. Your mom. Then you. You and your mom are probably the first girl lighthouse keepers.” He grinned. “I bet the ones before Jackson were all dudes, too.”

“I’m not going to be a lighthouse keeper. And I don’t think it’s been here that long.”

“You’d be surprised.” He plunged his hands back into the sink and came up with a spatula, made a face, and traded it for a fork. “Maybe when we’re done with the dishes, you can take me up there. I bet the view is awesome.”

“Take you to the lighthouse?”

That was absurd. Out there, the no-guest rule counted double. And getting past the traps was hard enough without dragging along some staircase rookie. Flustered, she picked up the plate she had just dried and was about to decline, as politely as possible, when her mother came through the door carrying two coffee cups with handles like flower stems.

“Here are some more, if you wouldn’t mind.”

Behind her came Patrick. Hannah felt herself turning red. The fact that Kyle had even mentioned going to the lighthouse made her feel like she’d just been caught stealing from her mother’s purse.

“We were just talking about the lighthouse,” Kyle said. “About maybe checking it out, if it’s okay.” Hannah stared at her featureless reflection in the plate. Did Kyle even realize what he was asking? She braced herself for her mother’s mood to plummet, for the chilly absolutely not to smack Kyle in the face like an arctic wind.

But her mother did something curious and completely unexpected. She turned to Patrick and raised an eyebrow. He looked at her for a moment, then nodded very slightly, just a quick bob of his head.

Leanna Silver practically beamed. “I’m sure Hannah would love to take you once you’ve finished with the dishes.”

This time, Hannah really did drop the plate.

The garden path was enclosed by a tunnel of trellises woven with flowering vines. On sunny days the light came through in millions of tiny patches that made a mosaic of white and yellow on the ground. At night the tunnel made the darkness deeper and blacker, blotting out the nighttime sky and any stars that happened to peek through the clouds. Hannah could sprint blindly back and forth to the lighthouse — she’d been doing it all her life — but her mother had insisted she take a flashlight to escort Kyle.

When they were almost to the end, Kyle stopped walking and took a deep breath through his nose.

“I’ve never been to the ocean before. It’s definitely got its own smell.”

“Brine,” Hannah said. Whenever she read a book that took place near the sea, people were always calling it briny. In English, she guessed the word meant something like “fishy” or “salty.” In Muffin Language, she decided, it would mean “the sound of a boy smelling the air.”

>

That’s a good one, Nancy said, genuinely excited for the new word.

Hannah had been enjoying the walk, but when she pushed open the door to the lighthouse, anxiety swelled. How was she going to handle the stairs? If Kyle didn’t already think she was a friendless weirdo, wait until he watched her skip steps, perform self-checks on her limbs, and dodge invisible torture devices. And the password! Once they reached the landing, there was an entire sentence in Muffin Language that had to be spoken with authority. Only then could they climb the short ladder to the bell-shaped glass room where the lamp sat dormant.

Inside, she turned off the flashlight and flicked a light switch on the wall. There were no windows in the lower part of the lighthouse, just the metal staircase spiraling up the center of a gradually narrowing tube.

“We gotta go up if you want to see anything,” she said, her voice cracking.

“Lead on, Miss Lighthouse Keeper.”

Hannah turned and glanced at the bottom step. One: an odd number. Just above it, step two beckoned like a warm embrace. Both Belinda and Nancy began to chatter, the old woman urging her once again to disregard this game, Hannah’s twin encouraging her to make it even more complex by adding math problems along the way. Their voices were impossible to ignore outright, but they could be shoved to the back of her mind. The problem was, this act of will made it hard to move her body. She lifted her foot with a jerky, robotic motion and placed it on the first step, conscious of the way she looked to Kyle, standing just behind her. He asked her something, but she barely heard him as she closed her eyes and moved to the next step. If she kept them closed, maybe she could pretend the traps weren’t there. And if the traps weren’t there, they couldn’t hurt her. As long as she moved very methodically …

The Escape

The Escape The Execution

The Execution Conspiracy

Conspiracy The Door

The Door